Why At-Home IPL Doesn't Work for Dark Skin: The Physics of Melanin

Navigating the safety-efficacy gap in at-home permanent hair removal for melanin-rich skin.

Note on Terminology: While I sometimes use the term “permanent hair removal”, which is often used in casual conversation, I am actually referring to “permanent hair reduction” as classified by the FDA. Per FDA guidelines, photoepilation (laser, IPL, and LED hair removal) is officially classified as “permanent hair reduction” which refers to a stable, long-term decrease in the number of hairs regrowing.

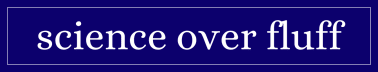

For those of us with darker skin (Fitzpatrick IV or higher), the at-home permanent hair removal market can often make us feel like an afterthought. Most at-home devices are based on IPL (intense pulsed light) technology. Some claim to be “safe” for our demographic but achieve that safety simply by dialing back the device’s power, called “fluence”, to a level where the treatment is no longer effective. Driven by the frustration of this “safety vs. efficacy” trade-off, I took a head-first deep-dive into the physics of photoepilation (light-based hair removal) to understand why those with darker skin are so left behind.

Standard IPL devices have a fundamental hurdle: they release a broad burst of energy into the skin all at once. Because melanin-rich skin absorbs that energy instantly as heat, the process is often painful and carries a high risk of burns or other unwanted side-effects. Engineers have attempted to bridge this gap through features like active contact cooling to protect the skin surface and filters to block the specific wavelengths, or “colors”, of light that cause surface damage. These features significantly reduce the harsh “rubber band snap” sensation, making the experience more tolerable. However, comfort is not a substitute for results. Even with these upgrades, IPL is often inefficient for deeper tones because the devices must throttle their total power to remain safe, frequently resulting in a treatment that is too weak to be effective.

Within the last few years, several IPL devices have entered the market claiming safety for Fitzpatrick IV and V skin. As of 2026, however, no at-home IPL devices are officially rated to safely treat Fitzpatrick VI skin. While IPL can be highly successful for “optimal” candidates (those with high contrast between dark hair and pale skin), the reality shifts as skin tones deepen. For those with a complexion beyond Fitzpatrick III, the physics of broad-spectrum light becomes a liability: these devices are statistically more likely to cause surface burns and less likely to deliver the permanent results they promise. To understand why this technology often fails us, we have to look at the science of selective photothermolysis.

The Science: Selective Photothermolysis

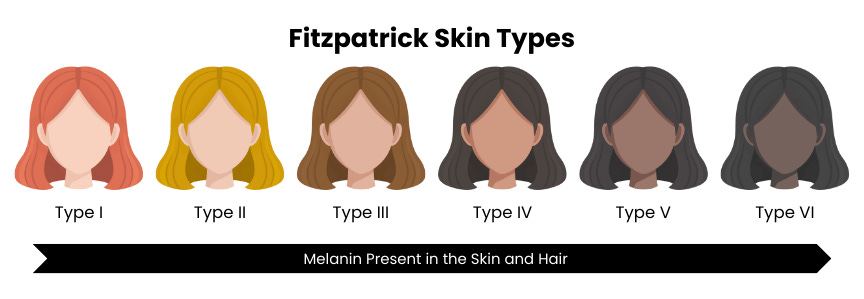

The primary “mechanism of action” of light-based permanent hair reduction is selective photothermolysis, a process designed to thermally damage the hair follicle while sparing the surrounding tissue. This works because the device emits specific wavelengths of light that are highly attracted to melanin, the natural pigment that gives hair and skin its color. When the light hits the target, the light energy instantly converts into heat. If enough heat reaches the base of the follicle, the hair-producing cells are destroyed.

Safety is maintained through the distinct thermal properties of skin and hair. Because the melanin particles in the skin are microscopic, they have a very short thermal relaxation time (the time it takes for tissue to lose 50% of its heat). This allows the skin to shed heat into the surrounding area almost instantly. In contrast, the hair follicle is much larger, meaning it holds onto that heat for a longer duration.

This process is supported by the skin’s high water content. Water has a high thermal capacity, meaning it takes a significant amount of energy to change its temperature, much like how a large lake stays cool even on a hot, sunny day. Together, these factors create a safety window: the light pulse is timed to be long and powerful enough to destroy the hair, but gentle enough that the skin can dissipate the heat before any thermal damage occurs.

The Catch: Because darker skin contains more melanin, the surface of the skin absorbs a significant portion of the light energy intended for the hair follicle. While pale skin only has to dissipate a small amount of heat, darker skin must manage a much higher thermal load. If the heat absorption exceeds the skin's ability to shed it, burns or other side-effects can occur. While specialized features can help bridge this gap, they often struggle to overcome the inherent limitations of IPL technology.

The Market Gap: Barriers to Effectiveness

Current IPL devices often struggle with dark skin for several reasons including:

1. Inefficient Wavelengths

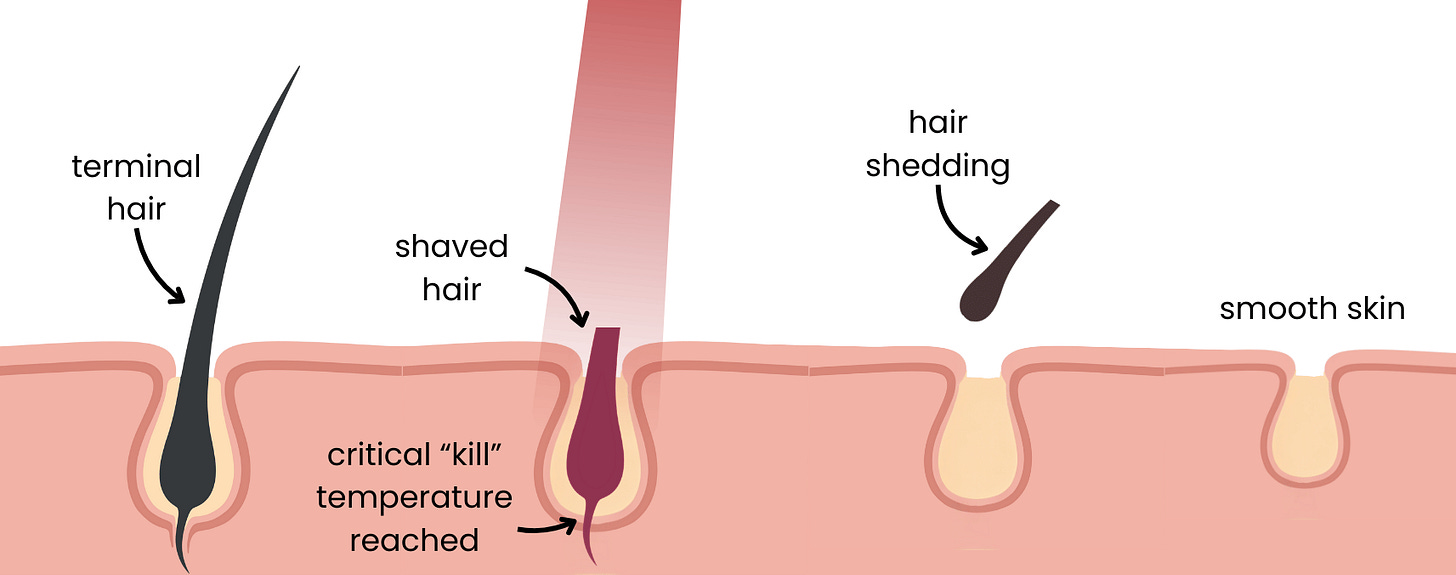

Light colors are measured in wavelengths across the electromagnetic spectrum; 400nm is a violet color while 700nm is a deeper red. Humans generally cannot perceive light below 380nm or above 700nm, but those wavelengths can still hurt your eyes which is why many at-home photoepilation devices come with safety glasses.

In the context of hair removal, different wavelengths have different effects and finding the “sweet spot” is essential for both safety and results. Unlike a laser’s single wavelength, IPL emits a broad “rainbow” spectrum of many wavelengths (500nm–1200nm). The challenge for darker skin lies in the physics of this spectrum: shorter wavelengths (500nm–600nm) are aggressively absorbed by melanin, which can cause darker skin to overheat before the energy reaches the root. Furthermore, melanin absorption significantly drops off at wavelengths above 940nm. While specialized lasers like the 1064nm Nd:YAG laser can utilize higher wavelengths, they require a much higher fluence to be effective. This is a power standard that small, at-home IPL devices simply cannot safely or efficiently replicate. While higher-end IPL devices try to “clean up” the light by filtering out the most harmful wavelengths, this approach is essentially a compromise; simply removing the bad light doesn't create the “right” light. Research has shown that targeted wavelengths or specific, narrow ranges are inherently more efficient at destroying the follicle than a broad-spectrum beam that has been stripped down.

2. The Fluence Problem

To achieve permanent results, hair follicles must reach a specific thermal threshold. This requires high “fluence” (measured in J/cm²) which is the concentration of energy delivered to the skin. For the “ideal” user (dark hair on pale skin), the threshold for permanent follicular destruction is generally around the upper limit of at-home IPL capabilities, at roughly 5-6 J/cm². This is the bare minimum efficacy in virtually all published literature. For context, professional-grade machines often operate between 20-40 J/cm².

Because dark skin competes with the hair for energy absorption, many devices automatically throttle power on deeper tones to prevent injury. When this happens, the energy is frequently insufficient to kill the hair follicle. When IPL has any results at all at these lower levels, the energy is more likely to trigger the hair to shed or enter a dormant phase. This leads to temporary smoothness rather than permanent reduction. In some cases, sub-therapeutic heat levels can even activate dormant follicles, resulting in increased hair growth rather than reduction, a phenomenon known as paradoxical hypertrichosis.

3. Short Pulse Durations

For dark skin, the duration of the flash (the pulse duration) is the safety factor that consumers most overlook. Research has shown that longer pulses make treating darker skin significantly more comfortable and effective; they allow the epidermis time to dissipate heat while the follicle retains heat and gradually reaches the necessary “kill temperature”. If you’ve ever wondered why some devices hurt significantly more than others despite having similar fluence levels, pulse duration is often the culprit. However, there’s a catch.

As mentioned previously, selective photothermolysis relies on hair follicles heating up enough to destroy the hair root. This process works because hair has a much higher thermal relaxation time than the surrounding skin. The exception is finer hair. Because finer terminal hairs have a lower volume and smaller diameter than thicker hairs, they lose heat to the surrounding tissue much faster, resulting in a significantly shorter thermal relaxation time. This creates a brutal engineering trade-off for manufacturers:

Pulse is too Short: Pulses deliver energy faster than the skin can cool, causing significant pain and burn risks for darker skin.

Pulse is too Long: Pulse durations become ineffective at treating hair on the finer side across all demographics, as the heat dissipates from the thin follicle before it can be destroyed.

There are solutions to this; professional IPL devices, in contrast to at-home devices, are able to extend the effective pulse duration for darker skin while maintaining a steady fluence by “stuttering” the pulses (firing several micro-pulses in rapid succession to build heat in the hair slowly). However, the electronics required to do this are sophisticated, expensive, and bulky. Consequently, commercial at-home devices lack the hardware to mimic this multi-pulse delivery. This forces a compromise: manufacturers stick to shorter, aggressive pulses that protect device performance ratings, but leave them needing to throttle power to safely treat melanin-rich skin.

4. The Physics of Divergent Light

IPL differs from professional-grade lasers due to the properties of divergent light. Lasers produce coherent light, meaning the waves are synchronized to travel in a perfectly straight, narrow column which reduces energy loss at the skin’s surface. In contrast, the incoherent light produced by IPL results in a beam that naturally diverges, or spreads out, in a wide and chaotic pattern.

Because these light waves are out of sync and travel in multiple directions, they often reflect or refract the moment they hit the skin. While this “scattered” light can still achieve permanent hair reduction in fair skin, it presents a challenge for those with darker skin. Not only does the light struggle to reach the follicle due to this surface scattering, but the melanin in the surrounding epidermis simultaneously absorbs what remains. This combination of optical scattering and competitive absorption makes IPL significantly less efficient and far more prone to adverse side effects for melanin-rich skin.

Conclusion: Bridging the Gap

Ultimately, the challenge for those with darker skin is a lack of options that consider our biology. The “safety vs. efficacy” trade-off in the current IPL market forces darker-skinned consumers to choose between a device that is safe but essentially a “glorified flashlight,” or a device that is powerful but poses a genuine risk of hyperpigmentation and burns.

True progress for our demographic lies in moving away from the current approach of broad-spectrum IPL and toward technologies that prioritize longer pulse durations and targeted wavelengths. By understanding the physics of our skin, we can stop settling for temporary hair shedding and start demanding technology that provides the permanent results it actually promises. We don’t need “safer” versions of the wrong tools; we need tools built for our melanin from the ground up.

Understanding the physics of the ‘melanin trap’ is only half the battle. If IPL isn’t the answer for brown skin, what is? I spent weeks digging into the specs of non-IPL technologies to see if any could actually bridge the safety-efficacy gap. You can read my technical deep-dive into the solution I found here.

Disclaimer: While I am an engineer and enjoy breaking down the science of how technology works, I am not a medical professional. The information shared here is based on my independent research and technical analysis intended for educational and informational purposes only. Please consult with a qualified professional before starting any new treatments or protocols.

Enjoy this article?

Follow Science Over Fluff on Instagram | Subscribe to the YouTube Channel

This is fasinating work on melanin physics and light interaction. The selective photothermolysis explanantion really highlights why the thermal relaxation time difference matters so much - but I dunno if manufacturers will ever prioritize longer pulse durations when they can just slap 'safe for all skin types' on cheaper hardware. I spent way too much researching at-home devices last year and ended up with one thats basically a glorified flashlight. The coherent vs incoherent light section is particularly eye-opening.